Disorderly Conduct

Text: Gabriel Knowles Images: Disorder Disorder

Text: Gabriel Knowles Images: Disorder Disorder

There are those amongst who can see the bigger picture, politicians for example unfortunately the perils of power means they’re not the best examples to off. The best examples are found in the community, working away to better those around them. Joseph Allen Shea is one of those people, as a curator Joe is acutely aware of of the role he plays in bringing new experiences into other’s lives and the power of connectivity. He sat down with Gabriel Knowles to explain why he’s taking his biggest show yet outside of the metropolis.

Gabriel Knowles: So how’d this show come about anyway?

Joseph Allen Shea: This one came about because I have a friend at the MCA, Glenn Barkley. I was just asking him about what institutions would be open to doing something that I’d be interested in – a bit bigger. And he’s a big supporter of what I was doing and he was always checking out what I did. And then he introduced me to the guys at Penrith and said you could check out this guy. Then they came and saw me and came and saw a couple of shows that I was doing at Monster Children Gallery and said ‘what would you have in mind?’. I proposed this large-scale show which was really massive when we started – I was like ‘Yeah! 60 artists!’. It was really over the top.

GK: But you’ve scaled it back?

JAS: Yes we’ve scaled it back. But we’ve still got 20 artists in the show. It’s still quite a big show. Ten of them are international. Ten of them are Aussie. And then every artist has got a bunch of ephemera that we’re going to show; other projects that they’ve worked on, commercial projects or self-initiated projects that include their fine art but wouldn’t be considered their ‘fine art’. So as the director of the gallery there said it’s like a 40 person show. There is a lot of works. I’m not sure, I haven’t counted the works but there must be… there’s well over 100 pieces.

GK: Wow.

JAS: Well over, yeah.

GK: I’m pretty interested in your background and choosing to go with the self-taught artists. I know you’ve talked about this before, but I feel like this is taking it to a new level.

JAS: Well I feel an affinity with all these guys because it’s the same background as I’ve had. My background is graphic design, that’s what I studied. But my cultural background is skateboarding and dabbling in surfing. I was a pretty committed surfer when I was a kid, from the ages of 11-19.

GK: You grew up on the Northern Beaches right?

JAS: Yeah. So I was out there.

GK: You’ve got no choice…

JAS: Oh my God! Three times a day, four times a day, on the weekend. I surfed a lot as a kid. And then always skated. Well I skated first, then got into surfing, but always had skateboarding. Moved to London and forgot about surfing, skated a lot. And just kind of ended up, through graphic design I was working for music labels and being a designer on King Pin, which is a European skate magazine that was printed in four languages. And then was hanging around all these dudes that were making art. It was really this collective called Side Effects of Urethane, they would put on shows that were skateboard related and really reinterpret the landscapes as well. So they would make these sculptural structures that were skate obstacles, but were also amazing sculptures.

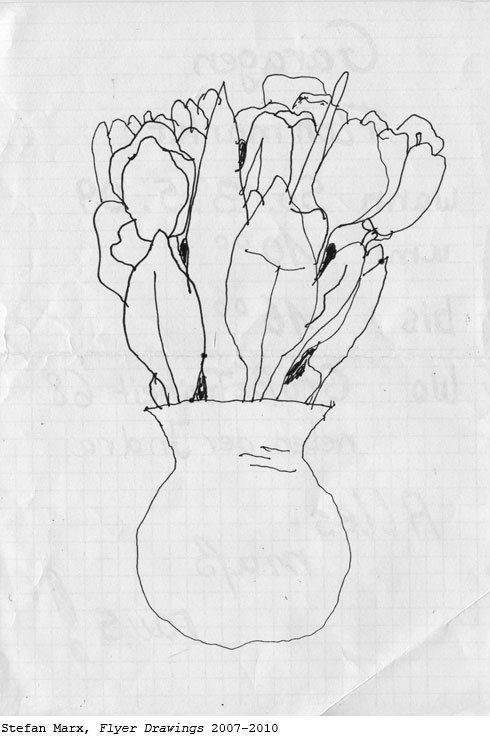

GK: Like the Stefan Marx piece?

JAS: Well they never did a Stefan one, but that’s the kind of thing we’re talking about. Stefan was doing his own thing anyway. He was involved in those shows but usually flat works, paintings and what not. But those guys really inspired me and that’s when I wanted to do the publishing thing because I felt like so much of that was under-represented. And I was a part of that scene, but I was more a viewer and an audience member. You know it was all very inclusive and all very proactive and I wondered how I could contribute. I had my graphic design skills and knowledge of this work and an interest that had been longstanding. So I started printing these books and zines and that’s really how that came about. When I returned to Sydney I was already working for Monster Children magazine, sending stories from London since the first issue. So they knew me, they’d just opened this gallery, realised there was a lot of work to be done and I took over that role. So I kind of just fell into it.

GK: Do you see that as having the same theoretical principles as publishing, where you’ve come from and now moving into the curatorial side of things?

JAS: Yeah it still feels like presentation of art.

GK: Just via a different medium?

JAS: I’m interested in working with artists and presenting art, so yeah I do feel it’s very similar. They’re both physical entities, they’re just different shapes and sizes to me. The gallery versus the book. That was easy and they go hand in hand. I mean if you could print a catalogue for every gallery show that would be the dream. I would love to do that. But back to your earlier question, which was ‘why these artists?’ Maybe I did answer it already but I guess being self-taught…

GK: Is there something in the mindset about coming from a different perspective? Why does that appeal to you?

JAS: Because… I’ll probably talk about skateboarding more than anything, because that’s my main passion and my main focus. But also I think it’s the most supportive, creative culture out of these, if we’re talking about subcultures right now. If we’re talking surfing, if we’re talking graffiti, if we’re talking art and music or commercial arts. If you’re a skateboarder you’re expected to make things. It’s almost as if by being a skateboarder you’re told you’re an artist, and that doesn’t mean that everybody’s a great artist, but it at least gives you the confidence or the platform to express yourself. To say ‘look you should just at least try’. So you know, a lot of terrible art comes out of it as well. But that’s not really the point. The point is that everyone’s making stuff and is supported to make things and skateboarding is a very creative activity as well because it’s about reinterpreting. If you’re street skating it’s reinterpreting what exists and how do you approach something differently and make your tricks stand out from what exists. Or how do you use a spot that may have been built for something else, like a loading ramp or a set of stairs or a handrail, and reinterpret that? Skateboarding took a real turn in the early thousands to be this…

GK: It’s a huge industry now.

JAS: Yeah industry-wise it’s been pretty massive for a while. But I think what I’m trying to get at is also the way skaters started trying to look for really interesting spots. I think that changed. You know I think it’s always been there but skateboarding went through a time when it was super technical and there was crazy hammers, big rails and stairs, and then it was like ‘well what next?’. So it became about finding the weirdest shit that exists and working out how you ride that. I think that was really interesting. It’s almost like a combination of all those things right now: weird things to skate, really heavy hammers and then technical skateboarding all at once.

GK: So I guess you could say it’s about a way of looking at the world.

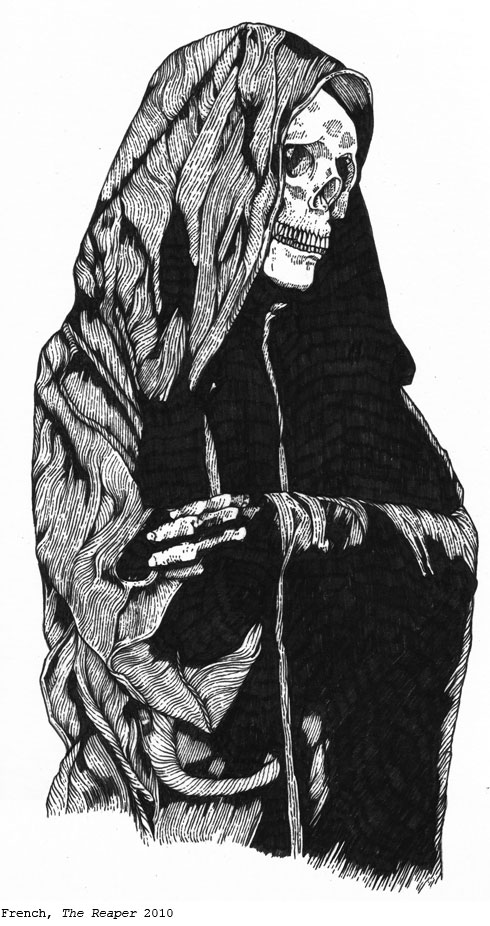

JAS: Yeah and a real DIY thing as well, and a real ‘get off your arse and something’ attitude, which I’m sure came through skateboarding’s ties with punk music. You don’t need permission, so make it your way. That’s an empowering aspect of a lot of these artists where they’ll do things regardless of a system in place. And that’s why this art is really interesting to me. Because they’re not all self-taught artists and they’re not all non-academic, if you like, but they all have this core motivation that came regardless of what was happening in the fine art world, what was happening in the gallery system, what was happening in the schools. They all took it from inside themselves.

GK: As opposed to outside motivations?

JAS: Yeah. Even someone like Ricky Swallow, who’s obviously in major museums and in the Venice Biennale and what not, he studied drawing but all the sculpture stuff was all self-taught. He bought a How To Carve Realistic Birds book and taught himself as if he was a hobbyist.

GK: Really, I didn’t know that.

JAS: Yeah. That’s why he’s in the show, but he also has a pop-culture background, he loved rock music and folk music and he was a skateboarder when he was a kid. Not that that really comes through in the work but I still think it comes back to that motivation thing.

GK: How many artists come from a skateboarding background?

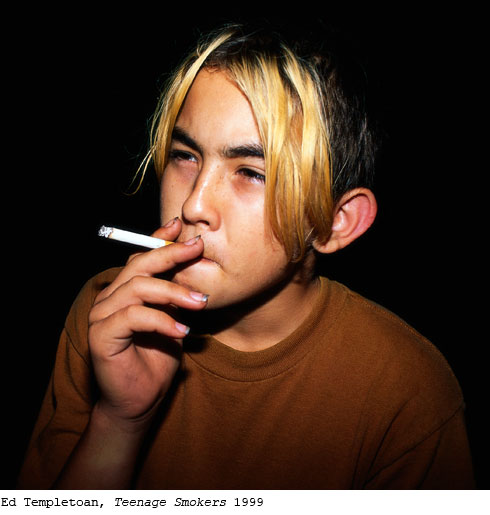

JAS: I mean some. Chris Johanson, all of his works are about skateboarding in this show. Which he has done before, but he really took it as an opportunity to make art about skateboarding, which is cool. And Ed Templeton… probably a lot of these guys, even if they’re not related to skateboarding, they probably did skateboard in the past and I feel like that is a pretty common link.

GK: A common thread.

JAS: Yeah, but it’s not really one that I am playing up.

GK: When you approach some of these guys do you say to them roughly what you’ve just been explaining to me – that there’s a premise behind what you’re trying to achieve?

JAS: Mildly. I think it was basically just art that came from outside the art world.

GK: Would you say it’s outsider art?

JAS: I don’t really feel comfortable with that term, because it has a strong connotation. But I think even ‘outsider artists’ – all people writing, all people documenting or showing outsider art don’t even like that term, because it’s really hard to categorise.

GK: It’s harsh.

JAS: It’s harsh and also it has a lot of reference to learning disabilities as well. A lot of connotations to artists with learning disabilities which none of these artists have… well maybe some mild dyslexia. But outside-ness or outside the system is definitely a quality…

GK: Outside-ness art?

JAS: Yeah other-ness art? I don’t know. It’s definitely something I’ve been conscious of and something I’ve been trying to define, but it’s been very difficult.

GK: Would it be wrong to define it?

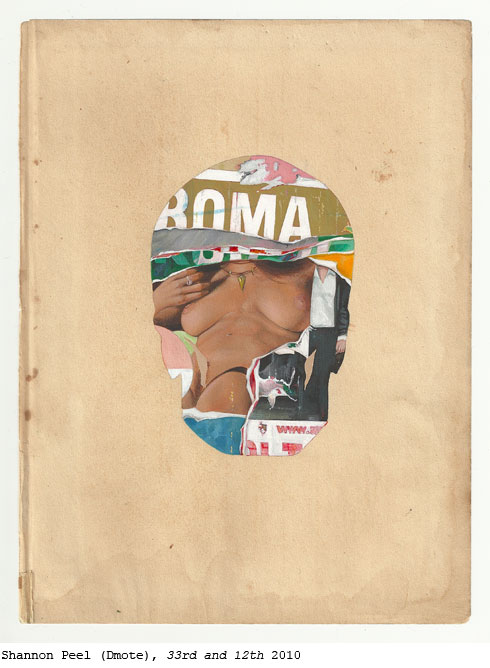

JAS: To define it at all? It’s definitely difficult to put a label on it. It does feel early I guess. In the catalogue there’s an interview with Alex Baker who’s worked with a lot of these artists before, but he’s also the senior curator of the NGV. We talked and I asked him how he felt about labelling these artists and is it too early? People have called them the Beautiful Losers movement, I’ve heard the word ‘transitionists’ thrown around.

GK: Transisitonists?

JAS: Yeah. It was coined by Chris Rubino and Deanne Cheuk when they edited Theme magazine. So artsist that kind of work across commercial platforms as well as fine art platforms. I don’t know though.

GK: Transitionist could be a skateboarding reference too.

JAS: Oh yeah, right. I think though it’s more about being able to transition between those two areas. Jonathon Zawada was in that issue, Stephen Harrington maybe… I don’t know. I think you’ve got to wait and see what time does really. What time does to this group of artists and work it out then.

GK: How close are they? A lot of the guys in this pool? Are they acutely aware of what the others are doing or not?

JAS: I would say yes. There’d be a couple but I mean most of these artists would know and understand of each other’s work. Especially, there’s maybe an age bracket of between 25 years from oldest to youngest artist. So some of the older, more established, American artists may not know about some of the more emerging Australian artists that I’ve put in the show, but those emerging Australian artists would definitely know about the elder statesmen of the show. There’s definitely these areas and a lot of the artists would have shown together, shown in similar galleries and been in group shows. But several of these artists haven’t shown in Australia. It’s quite a big thing.

GK: Who hasn’t shown here?

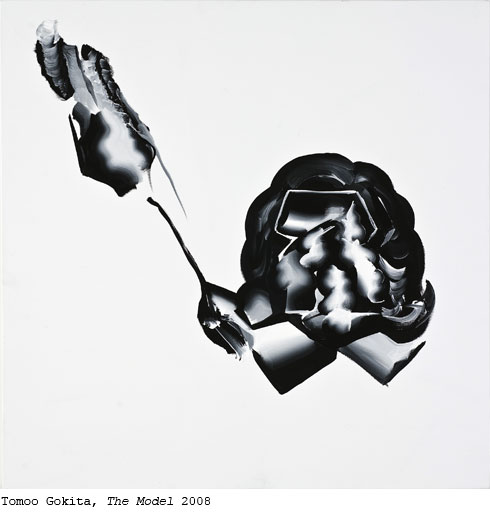

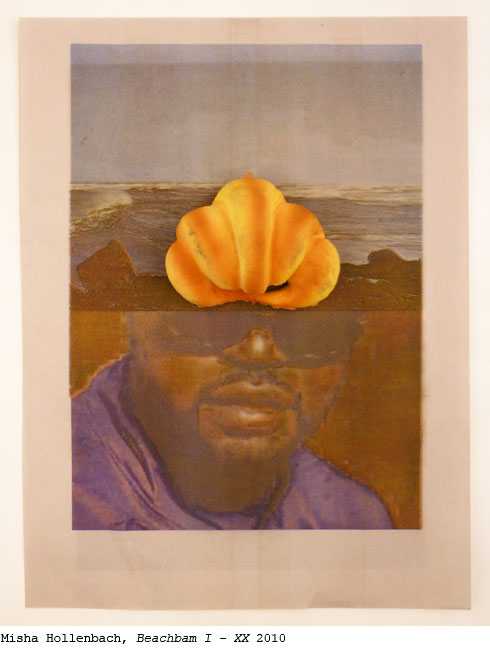

JAS: Jacob Ciocci from Paper Rad is in the show, he wouldn’t have shown here; Chris Johanson has shown here, The Gonz has shown here. I think it’s just lumping them together in a big institutional show that hasn’t happened before. They’ve done smaller shows here though. Chris Johanson showed with Pot i Gold, which was Misha Hollenbach’s shows that he did in Melbourne 10 or 15 years ago. The Gonz had a show at Our Spot with Lee Ralph a bunch of years ago, but there’s been big gaps and putting it into the fine art institution hasn’t really happened at this level in the past.

GK: I guess what I was getting at in asking if they are aware of each other’s work. Do you notice things like them referencing each other or maybe they’re influenced subconsciously?

JAS: Yeah I would definitely say that there is a lot of this. And because several of these cultural activities, like skateboarding or surfing kind of stemmed out of California, a lot of these artists like Mark Gonzales and Chris Johanson, they’re definitely a part of what happened and is happening in that part of the world where everyone’s looking towards. So skateboarding came from there. Surfing came from there and you get these… It’s almost like… well, I’m trying to avoid labels again, but this modern Californian folk-art kind of thing. It kind of resonates out of there as well and you’ll see that in the works of Kill Pixie for example – the back coloured stuff and the patterns and the decorative motifs I feel that’s sort of a lineage from there even though it doesn’t really look like anything I know from there as a whole, there’s individual elements. And definitely in his earlier works you’ll see it. But now his voice is becoming stronger and he’s got his own thing going on.

GK: Is that a rewarding aspect, seeing someone you’ve collaborated with over a long period of time developing such a strong voice?

JAS: Yeah I mean rewarding… it’s exciting. They would have done it without me. I get excited whenever he has a new show, especially if it’s somewhere else in the world or a big prestigious location. That’s always very exciting for me but part of that is on a friendship level. I mean we’ve built a friendship out of working together. So I guess it’s more personal than it is… I don’t know if you’d call it business or career… I don’t know what you want to call it.

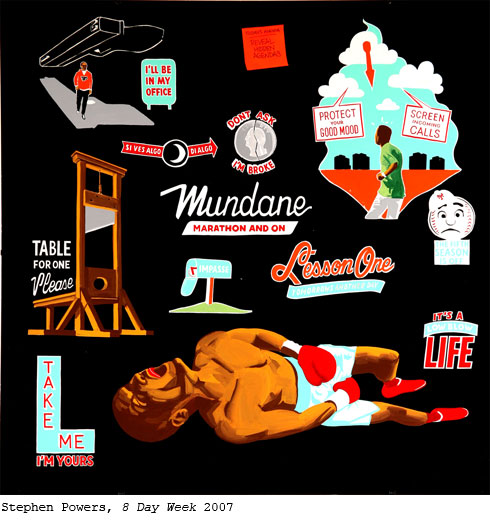

GK: What about this residency thing you’re doing with Espo/Steve Powers?

JAS: Yeah that’s super exciting. A bunch of your readers would know he’s done a lot of these public projects with communities. He just did a big one in Philadelphia, along the train lines, the Love Letter project. He teamed up with youth in Dublin as well to create new works and murals to work with youths there and their political issues, there’s a big history of political murals there. So we’re taking him out to St Mary’s to work with the community and make signs inside the community to know exactly what will come from this, who this guy is, because most of them wouldn’t know his background. To know exactly what will come from this is hard to decipher at this stage. We’re going to do workshops with kids in St Mary’s and make signs with them and he’s going to have a shopfront space where he can work making the signs and displaying them in the community. But we’re really trying to excite the kids who write graffiti as well. It’s very exciting.

GK: I would imagine that a nice outcome out of this might be that it would inspire a lot of those kids to pursue it further?

JAS: Another way to speak with different audiences is very exciting and if they can find a way to make it work in the community or in a gallery then that’s great.

GK: Do you think it’s important to exhibit these types of artists outside of inner-metroploitan areas?

JAS: Yeah, one of my main goals is broadening audiences and expanding how and where people see this work. We know that there are a lot of people making work in these massive areas and it’s important to show these artists in areas where they haven’t been shown before. It’s also important to show them in an institutional gallery rather than a small artist run space or through an “art dealer” and show it in an international context. Some of these artists have shown at the Whitney Biennial, or the Venice Biennale and are in major museum collections so for me it’s about expanding what’s happening in these smaller spaces because I feel like Australian art viewing audiences are super-conservative and haven’t been exposed to a lo of this work due to its other-ness nature. It’s not art about art, you don’t need to have an art history degree to understand it.

Disorder Disorder is showing at the Penrith Regional Gallery from August 14 until November 14

Next story: Abstract Concrete – The Butcher’s Daughter