Future Primitive

Text: Melissa Loughnan Images: Mark Rodda

Text: Melissa Loughnan Images: Mark Rodda

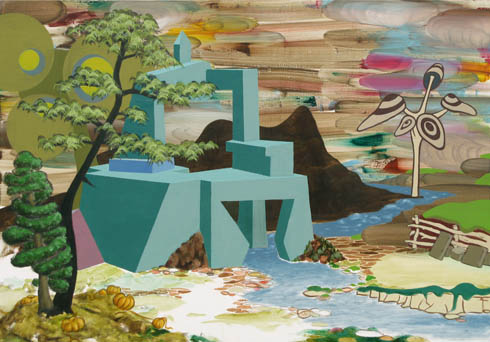

Tasmanian-born Melbourne artist Mark Rodda paints with a fervent fever; verdant, hillocky, often-imagined landscapes are accompanied by fictional characters and exotic plants. Where creatures and characters are absent it is as though they have only recently left, perhaps to shortly return, as their surrounds continue to thrive. Futurescapes are projected that encompass exotic and native plant species, an optimistic if not surreal future weighted by the legacy of eighteenth and nineteenth century European painting.

Rodda’s next solo exhibition, Sleeping Giants, will be held at Utopian Slumps from 1 to 23 April 2011. Melissa Loughnan caught up with the artist in the lead up to its opening.

Melissa Loughnan: Your paintings tend to move between geometric abstraction and loose landscapes, and sometimes a combination of both. What happens first, your conception of a style or working method, or the narrative behind a work?

Mark Rodda: I start my paintings in many different ways, from the intricately planned to the very unplanned. I usually work on at least half a dozen images at once. I often have a couple of ‘serious’ paintings that I have high hopes for, then another couple that are like ‘playtime’, where I put less pressure on myself and try to come up with something new. With my less planned landscapes I often start by painting a sky; a good sky can send a person into some interesting mental spaces. I might stare at these skies for half an hour or days before a clear path opens up before me.

ML: How has the Tasmanian landscape influenced your practice?

MR: I grew up in New Norfolk, forty minutes up the Derwent River from Hobart. The Derwent valley around New Norfolk is very hilly, very green, and often foggy and wet. In Winter I’d walk to school and pick up sheets of ice from the frozen puddles and smash them on the ground. I lived on the side of a hill and in every direction on the horizon were either very big hills or mountains. The landscape was very European, hops grew along the valley, and poplars, pines and willows dominated the parks. When I first moved to Melbourne I had a lot of trouble getting used to the flatness and the heat. I’m used to it now and I think Melbourne’s great, but I still have a yearning the type of land and climate that I grew up around.

ML: As you’ve mentioned, your work is inspired by the Tasmanian landscape, which is quite European. Which European painters are you particularly influenced by?

MR: Friedrich and Turner are big landscape influences for me. My favourite painter in terms of general attitude is Eugene Delacroix. Just by looking at his work you know he deeply cares about what he paints; art was never some academic game to him, it was all about hearts and souls. His diaries are published in a large book and it’s a really good read. Sticking with the French, Corot is great for me because, like me, many of his landscapes are fabricated. There is a particular rivers-edge scene he returned to frequently that is so beautiful but totally made up, pieced together from memories and other paintings. Another big influence is the spooky Norwegian painter Theodore Kittelsen, he has a creepy fairytale vibe and is featured on a few Black Metal album covers. The Pre-Raphaelite William Waterhouse is also a big influence, his Sirens painting is my favourite picture at the NGV. Also I’m a big fan of medieval painting in general, I love the skewed perspectives, the bizarre landscapes and plants, and the way that ‘important’ things and people have to be larger in a scene than everything else.

ML: Are there any contemporary artists/painters whose practices you follow, international or local?

MR: There are many great artists in Melbourne right now, but if I start listing names I wouldn’t want to leave anyone out so I’ll just leave it at that. I’m a big fan of the French abstract painter Bernard Frize. Julian Hooper from New Zealand has pictures that give off a welcoming energy. I’m a fan of super-cute Japanese art and design from artists like Murakami and Sugito. I also like the English painters Fiona Rae and Phillip Allen.

ML: You not only paint, but also work across video, animation and photography. How do these practices inter-relate?

MR: They sometimes don’t, in the past I felt like there was a war between my paintings and videos. But in the last few years there’s been a peace deal signed. All my mediums seem consistently interlinked now, mainly because they all involve plants and mysterious ‘other’ worlds. It’s great to have a second or third outlet, it can really help to briefly change medium if you’ve lost momentum. For a while years back I thought that I might become a short film maker, as opposed to a video artist, and I made a few animated videos, but the relative freedom of the gallery system always seemed more appealing to me so nowadays I stick with painting and video art.

ML: A number of fictional creatures come to life in your paintings. Can you describe the process of the invention of these characters? Do they relate to people or other aspects from your life or popular culture?

MR: My creatures never seem to relate to my real life, well not deliberately anyway, maybe subconsciously? I try to focus on universal, timeless themes rather than actual events. They all come from my drawing notebooks, if I was left to my own devices I’d scribble down line drawings of cartoon faces all day.

ML: Do these characters ever reappear in your work?

MR: Not usually, but I’d like to reprise certain created entities one day. It could become a painted soap opera.

Next story: Icy Focus – The Killing Words