Gods And Monsters

Words: Millie Stein Images: Samuel Hodge

Words: Millie Stein Images: Samuel Hodge

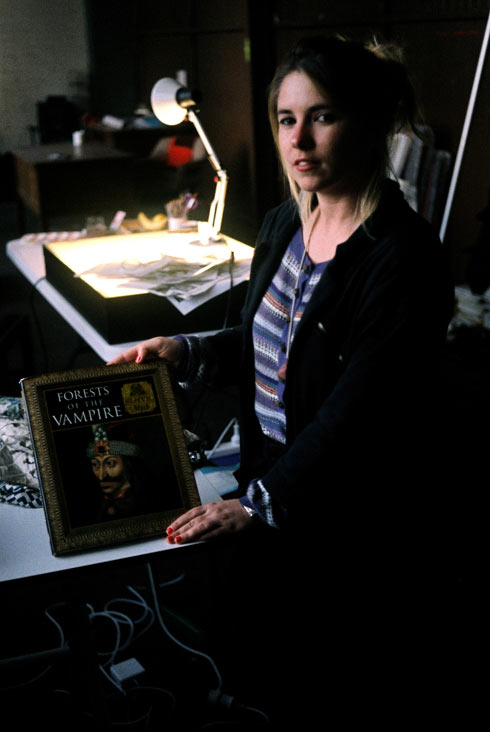

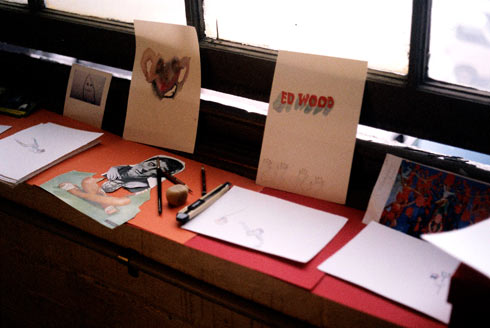

Tara Marynowsky fills her life with characters. They’re on her walls, on her desk and in boxes around her studio space. At any one time, she’s packing hundreds of archival images of ladies in a pantomime, dour-looking school children, two human halves of a horse suit and every face, shape and costume in between.

Then there’s her art – something like a back catalogue of imaginary friends and enemies, assembled semi-correlatively in groups, rendered delicately in watercolour. There’s softness to the images that Tara likes and makes. In her most recent series, Gods and Monsters, the unease of each group portrait scenario is tempered with flights of fancy, like the beautiful title character of Lady in Egg (2009) and the disproportionately large head being clung to in Holding On (2009).

“I kept looking at images of kids in school photographs and thinking how horrible it is, when you’re in school or in a school play and you have some weird costume on and feel really strange in it,” Marynowsky says. “I’m sure some people were into that, but I remember thinking, ‘Far out, what am I doing?’ When I am painting that kind of imagery, I’m thinking about how odd and lonely they feel, despite the fact that they’re in a group and dressed up to look ‘kooky’”.

While they might seem benign enough, Marynowsky’s characters have a flipside. They are skewed; the kind of folk that morph with a second glance. While they’re not altogether sinister, the faces are spectral and slightly unsettling. Take the boys in the back row of Cotton Eyes (2009), or Missing Person’s Jockey Club (2009). Actually, make that any of Marynowsky’s group paintings – it’s the ones in the back that you have to watch out for.

“With any of those images, you could say one character was a God and the other was a monster but you could also reverse it,” Marynowsky says. “A lot of the works I have done have been about good and evil, but they are also about what we worship. Some people worship God and some worship monsters and anyone could be either or.”

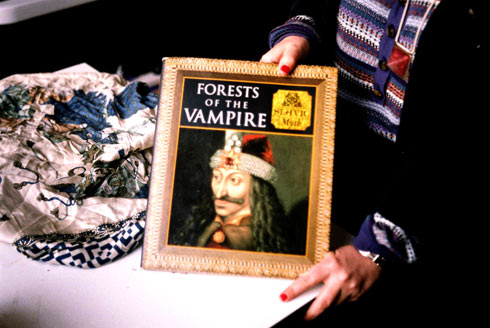

“I love old photos where there’s a ghost in the background, where they tricked people into thinking about the scary things in their lives. It’s interesting to think about how ghostly things come to be a part of your life, and for what reason. I’m influenced by myths, fairytales and old yarns, but in the same way I don’t like a lot of it. It sounds so childish. Although the more you read and the more you find out, the more the real strangeness of it comes out.”

Despite ‘good versus evil’ and other vaguely biblical ideas, nothing about Marynowsky’s paintings is directly religious. They lack that heavy, insistent feeling of art that relies on iconography to address issues of belief. Instead, Marynowsky utilises far less loaded aspects of tradition, like costuming, masks, pattern and colour, to free up interpretation.

A lot of the imagery in Marynowsky’s art comes from her own Slavic heritage. She recalls being frightened by a woodcut of Ukrainian poet Taras Shevchenko on her grandmother’s wall, and listening to countless stories in Ukrainian (which she doesn’t speak) about “some creature or some woman”. In that sense, Marynowsky’s characters have a very personal underpinning. But just as every fairytale and myth has its roots in a classic human dilemma, Marynowsky’s paintings are a creative rendering of every person’s complex relationship to the unknown.

“When I was a kid I used to look at this book of photos with ‘ghosts’ in the background – probably a chair behind the curtain – but it was a book, it was published, so it was presented as ‘fact’,” Marynowsky says. “I always found it funny that it was in the school library. It was interesting to me that someone had possibly believed in it. Again, it’s that idea of what you do and don’t believe in, and how you can use certain tools to influence the beliefs of others”.

“We think we are incredibly aware of everything now with technology, and that there is nothing to be afraid of in abstract. People are more scared of immediate things, like crime, and there is less of that supernatural feeling out there. I guess outer space is pretty amazing, if you want to think of it in those terms. It’s pretty fascinating and there is a lot of hope attached to it, where people like to be freaked out by it.”

The gravitational pull of something that scares you is at the core of Marynowsky’s art. Each character is good and bad, visible and obscured, traditional and modern. The dichotomies are right there on their faces, if you can look them in the eyes for long enough.

“I don’t really think about what they mean much,” Marynowsky says. “It’s more about the composition and making interesting creatures and characters work together in a space. I like the idea that you just reinterpret things for different purposes. I guess that’s kind of what I am doing. It’s about how you interpret all of the images in your life. I can’t imagine not wanting to have lots of things around me like that”.

Tara Marynowsky

Next story: Twerpentime – The Twerps