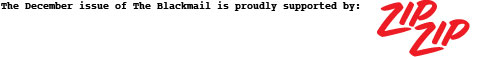

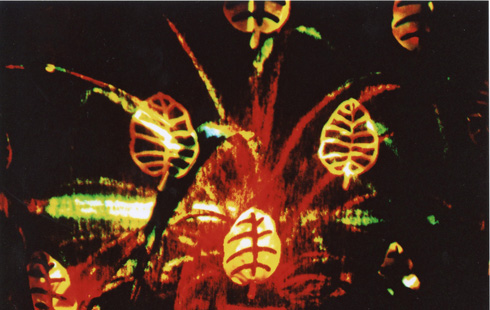

Moving Statics

Text: Millie Stein Images: Arthur & Corinne Cantrill

Text: Millie Stein Images: Arthur & Corinne Cantrill

Arthur and Corinne Cantrill started making films in Brisbane in the 1960s before moving to Melbourne in 1971. In the subsequent years they took their camera and reels all around the world, participating in dozens of exhibitions, festivals and screenings for their experimental (although they hate the word) short films and features. Their repertoire includes works on Super 8, 16mm and 3-colour separation.

Although the Cantrills rarely travel these days, their work remains in major international collections including that of the MoMA and the Musée national d’art moderne at the Pompidou. Their most recent show was a retrospective at ACMI where they presented 31 works (out of over 140) over four sessions.

As well as their films, the Cantrills published their magazine Cantrills Filmnotes for 30 years. The intention was to publicize obscure artists and filmmakers such as Xerox Dream Flesh and Ewan Cameron’s Theatre of Hell. They still have every back issue of Filmnotes stored in their house in Melbourne, in case you’re interested.

Buckminster Fuller once said: “I just invent, then wait until man comes around to needing what I’ve invented.”

One way of interpreting this would be to say that it speaks of underappreciated output. Isn’t Bucky saying that an artifact – a film, an artwork, a geodesic dome, etcetera – is only seen as valid once the period in which it was made can be retrospectively classed as a ‘movement’?

Actually, I don’t think so. What this quote says to me is that people may or may not come around to liking what you make. The important part is that you made something, and will continue to make things, in the first place.

Millie Stein: When did you first become interested in film?

Corinne Cantrill: We started filmmaking in 1960 but I think we’d both been interested in film, as well as film history and theory, before that. I have been an avid filmgoer since I was a child. I lived in Europe for quite a while from the age of 19 and had a deep immersion in film there. I was a member of a cine club in Paris where I went several times a week to the program they put on, which covered a wide scope of film history. In the early 1960s, we were living in Brisbane and we were members of the Brisbane Cinema Group. One of the people that ran it was already very familiar with the New American Cinema. He was probably the first subscriber in Australia. So we knew about Jonas Mekas and [Mekas’s magazine] Film Culture…

Arthur Cantrill: There was all this simmering in the background, but it took us a while to put it together and decide that this was the area we wanted to push in to.

MS: One of the recurring themes in your work is the idea of ‘power over things’. This was [Australian poet and philosopher] Harry Hooton’s idea, and is also central to your 1969 film about him.

AC: Yes, the application of emotion to matter, which was [Hooton’s] definition of art. Corinne and I both knew Harry Hooton separately before we met up, and he influenced us both in different ways. The materiality of film has always been important to us; pushing into different physical and chemical possibilities.

MS: Do you identify as artists as well as filmmakers?

AC: It’s always been a problem. We fall between the art establishment – who has difficulty in recognizing us as artists because even though they’re familiar with video art, they’re somehow suspicious of film art, or at least they don’t make any effort to exhibit it – and the film establishment, who has never taken us very seriously either. This is a problem that all film artists have, really. It’s slightly easier in some places: the MoMA shows work in this area, as does the Pompidou and centres in Germany. Even the word ‘experimental’ has been a problem for us, although these days we’re more used to the term ‘experimental music’ and somehow my soundtracks have been taken up by the experimental music community. The word ‘experimental’ has never been quite adequate to describe the work, I think.

MS: How do you prefer to describe your work?

CC: I think ‘film as art’.

AC: Len Lye used to call it ‘fine art films,’ and make it quite clear that he wasn’t talking about commercial art. It’s the medium that has no name, I always say.

MS: You showed films in two of [American performance artist and musician] Charlotte Moorman’s New York Avant-Garde Festivals. Can you tell me what that was like?

CC: We lived in America from 1973 to 1975. Our two years there were extremely valuable and we showed our work all over America and Canada. It was also very helpful in getting Cantrills Filmnotes published. I think the first time our work was shown in the Avant-Garde Festival was through Jud Yalkut, who was also closely associated with [long-time Moorman collaborator] Nam June Paik.

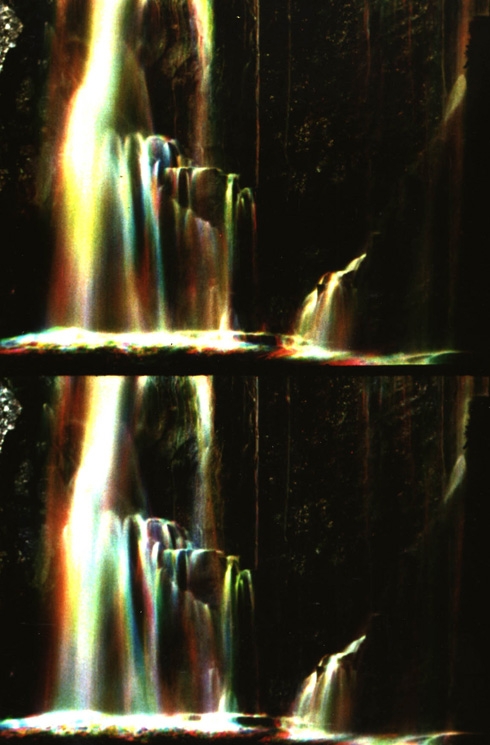

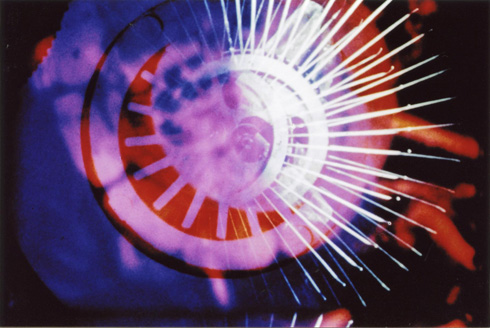

AC: I think it was Moving Statics that was shown the first year, but we weren’t present for that. We swapped our print for prints of Jud Yalkut’s and Nam June Paik’s films.

CC: We were living in America for the next Avant-Garde Festival, and Charlotte Moorman invited us to come up to New York and take part with a very elaborate multi-screen work called Skin of Your Eye, about the Melbourne counterculture.

AC: She was very businesslike when she was on the floor organizing this, and she said, “There you are, you can use that space there.” It was flooded with daylight and we said, “This is impossible for a screening!” We really couldn’t believe she had suggested it as there was no way of blacking it out. She said, “Well, look around and find a better place!” We found this storeroom, stuffed with dirty old seating. Myself and a couple of my students from Penn State University dived in and dug it all out. We were quite happy, but it was rough going – we had to sleep there on the concrete floor at Shea Stadium. But we were young then and we could do things like that.

MS: When watching work that you made 50 years ago, can you clearly recall what you were trying to achieve?

CC: I think so, yes, even though what we would have been trying to achieve in 1960 may have been much less interesting than what we were trying to achieve in 1975 or 1985.

AC: We’re very fond, and very uncritical, of all of them. I suppose we automatically, perhaps unthinkingly, hold back things that we think aren’t so successful. I’ve looked at Harry Hooton hundreds of times and I still love seeing it.

CC: But you mightn’t love seeing some of the very first films we made back in 1960!

AC: Ah yes, a volcanic eruption in New Zealand. Mud (1963) is considered to be the first experimental film ever made in New Zealand, but it’s a bit naïve and clunky.

MS: You don’t make DVDs of your films nor do you make them available online. Can you explain this emphasis on making your films a singular experience?

CC: I feel that some of the greatest cultural experiences in my life have been theatre, especially experimental theatre, and those were all one-offs. We have a huge volume of what we call ‘film performance works’ that we’ve made at La Mama Theatre in Melbourne since 1977. These were quite complex one-off works with filmmakers as protagonists. We had sound effects on tape and often the film was projected within a set that helped to extend it. We’d bring in trees, rocks and sand to create a landscape that would shadow the edge of the film.

We went in to these works because I became very interested in the nature of particular film screenings and the audience. Take Harry Hooton: we’ve shown that film many times, but there are particular screenings that stand out in your mind as being fantastic because of the audience. This is why I became interested in doing things in the theatre as an unrepeatable experience. If you’re there, you’re there – but if you’re not there, well, you’ve missed it. I don’t believe in permanence or any of those ideas. When you think of the terrible destruction that wars and earthquakes and heaven-knows-what have caused to art in the world… I think it’s an illusion that there is such a thing as permanence.

We’ve been to some incredible theatrical performances that only exist in our memories, such as Robert Wilson’s twelve hour performance of The Life and Times of Joseph Stalin in New York. Earlier this year, we went to something at La Mama about mathematics and the set was just extraordinary. It’s the same thing: you’re either there or your not there.

MS: What is it about film that continues to engage your interest over an entire career?

AC: The possibilities are never ending. Life is short and the art is long, as it were.

Next story: Chairs Missing – DB Project Space