Vertical Sleep

Words: Tristan Ceddia Images: Joshua Petherick

Words: Tristan Ceddia Images: Joshua Petherick

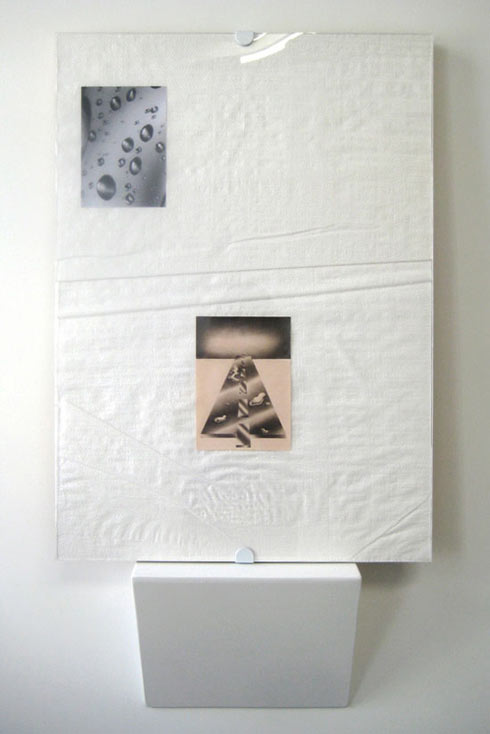

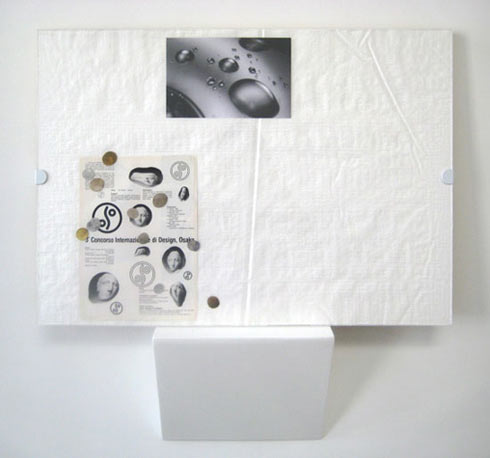

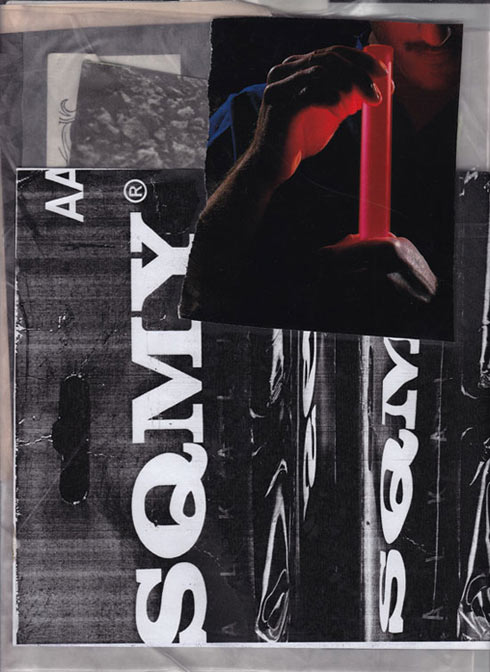

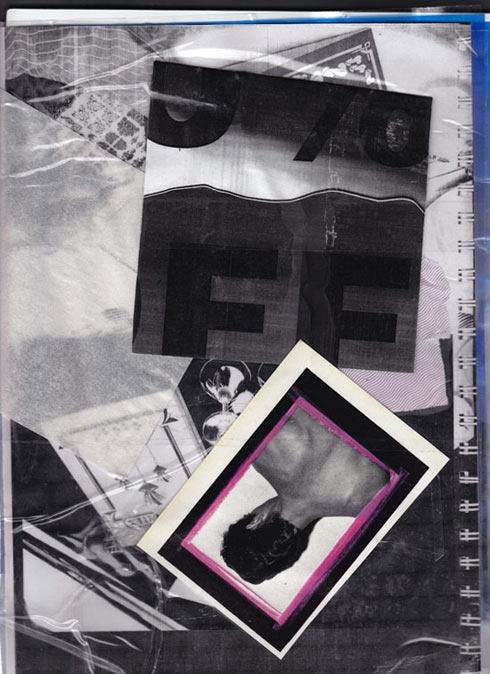

Joshua Petherick definitely has more than one leg to stand on. Artist, illustrator and founder of the recently opened World Books store at Y3K Gallery in Melbourne, he has shown work at the Tate Modern in London and colette in Paris. His work is like a puzzle consisting of elements that have been pulled apart and re assembled messing with your perception like a good inside joke. Tristan Ceddia asks Joshua some questions, and in turn, he answers.

Tristan Ceddia: On your website you are described as an artist and textile designer. Over the past few years, from what I can tell, you have moved your focus more into the art world. Was that always the plan?

Joshua Petherick: Not a plan, I’m not a good planner. My interests just pulled in that direction. It seemed the only place for what I was wanting to do, and it was my direct surrounding. It was becoming increasingly difficult to let the things I was thinking about (and making) breathe within any commercial “day jobs” I was doing for years. Apart from a few great people I work for in publishing and textiles (sadly, aside from projects with other artists and friends, they are all in European countries), it seemed next to impossible. Let’s face it, outside of some isolated exceptions, the state of contemporary Australian design is dull, at best. Sorry for my lack of tact. It would depress me though. So my activities developed more and more off to the side of my bill-paying jobs, yet were still very much informed by and concerned with my fondness for applied and graphic arts. Very much so, though I was starting to look at it from a particular angle that had me more interested in the potential of it’s “failings”, if you will – what comes from the breaking-down and the inadequacies of graphic and linguistic communication. The myths and fictions that accompany that. I was already thinking about these things through exhibition pieces and music projects.

Anyway, there is only so much just getting on with it you can manage when met with unthoughtful commercial clients. It feels to me right now that a very simple, radical thing one can do within this phantom standard of all-out economic pressure, is to stop and think about what they are doing and consider their positioning. To politely stop industriously getting on with it and size things up.

There was also a matter of energy. I wanted to explore the performative aspect of the image, of patterns, sequences, and all those accompanying questions of presentation, distribution, attribution of meaning. I had a real need for my work to pull back and loosen itself up. To make it both heavier and lighter at once. Does that make sense?

TC: Your work has become increasingly abstract, but not without purpose. If a person who had never seen your work asked you to explain it, how would you respond?

JP: My reflex would be to not. If pressed to respond in regard to any particular work I would probably talk around it – frame it’s becoming (theoretical, anecdotal, whatever it might be), but never speak for it. Artwork for me is not explanation; what excites me about a work of art most of all is what you can do with the areas of silence in-between what is gathered. It’s that subjective space that endows the viewer with a role in giving it it’s legs. A speculative bringing to life, if you will, beyond the meticulous play of material, process and gesture. That space is very important to me.

I think on a more general level any abstraction comes from what I said before about wanting to consider the performative nature of images – it brought on a real necessity a few years back to clear the board and reduce everything I was doing so that an idea can breathe and take shape anew. For me that shape has been about unraveling and exploring all the things I was thinking about and making in the margins of my commercial work. So the “clear board” became the support for bringing together a whole lot of mediums (drawing, audio, sculpture, print-production, painting, video) I’d been using to make, collaboratively and independently, seemingly disparate things and grasp their relationship for the first time. More and more I’ve been understanding these multiple lives in my practice and their operating and re-circulating throughout each other. Folding ad infinitum!

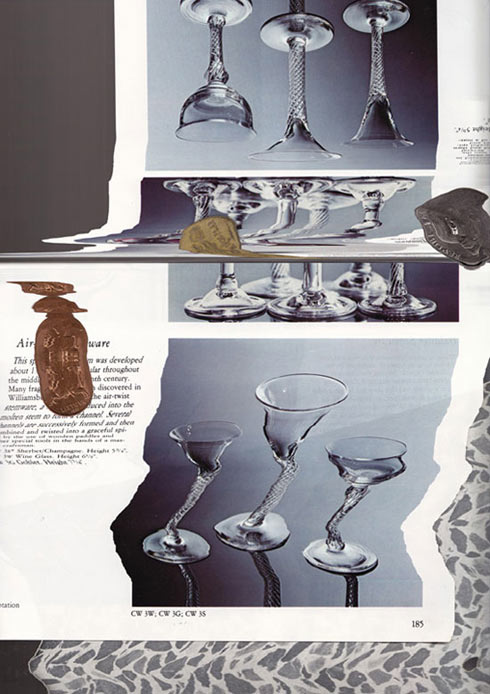

So I think the abstraction perhaps starts with the disruptions and interactions of those various elements after being brought to a completely reduced, unified point. It was conscious, but not an explicit decision in any way. I started to let technical processing that I was using a great deal in my graphic and audio work already play a clumsy and crucial role in the outcome of what I was making. So too these habits of gathering and layering. And chance. I started to let these procedures I enjoyed so much push the work around, and vice-versa, so that their functions and translations from media to media became an important factor in the weaving and abstracting of, say, the audio, with the transfer painting, with the sculpture, with the drawing, etc. It added to this contingency between all things I was using in my work.

TC: I know you lived in the Netherlands for a while recently. Did your time in Europe change they way you practice?

JP: Oddly enough, I went to a country of exorbitant arts funding for production to produce very little. Quite a paradoxical experience. For that reason it had a great lasting impression on what I was doing. By doing little. Being in Amsterdam and Rotterdam was more the instigation of my partner at the time, while I very willingly took the opportunity to take hermitage from a too-familiar setting and become the flâneur of an unfamiliar one. The sheer volume of projects, event-making, public programming, publishing going on there (for large quantities of better or worse) gave me a perfect setting to become an actively participating detached observer for awhile, and take myself some time, experiment with my work and be in dialogue with those around me. That pushed me forward a great deal. I didn’t realise it as it was happening; it was a strange time. A fruitful coma. I was voraciously looking and reading the whole time. The great thing about being in an unfamiliar place is that you look so much harder. I got back to reading anarchist literature because of the impact groups like Provo, Dolle Mina, even Dutch Fluxus, etc. had had on everyday life and law in The Netherlands. I read and walked a lot.

TC: Who or what would you say has had the biggest impact on you as an artist?

JP: The fact that you can sit and look at the same thing differently over and over again. Also, learning to use error.

TC: You recently had a solo show at Tolarno gallery in Melbourne and were in a group show at the Tate Modern in London. Is it intimidating showing at such big institutions?

JP: Not intimidating, possibly challenging, but mostly interesting.

TC: What is a typical day in the studio like for you?

JP: At the moment I don’t have a typical day, but ideally it would revolve heavily around the morning. I’m all for mornings. I dislike working at night-time. The quiet of working before lunchtime I find very satisfying. No-one hassles you in the studio, it’s a good time for meeting deliveries, reading, and it has the best light of the day. I’m quite dull in that I desire pretty steady business hours. The reality of that is not so straight forward however. My studio is behind our book shop, and also Y3K, so there are days made up of the various tasks of shopkeeping. It’s also a very social studio. Other days are more choreographed active work days – constructing things, checking on things, designing, moving piles about, all that. There are a surprising amount of days that feel like business, though. Email or meetings. I am really quite bad with telecommunications and I encourage it to some degree, otherwise those business days would stretch into every hour. There seems to be an excessive amount of reaching out going on between people.

TC: You recently launched World Food Books with James Deutsher in the foyer of Y3K Gallery, Melbourne. What is your involvement with Y3K?

JP: Officially, apart from a lot of things, nothing. I do sell books there, I show there, grow flowers with Chris there, amongst other things.

TC: World Food seems to be an ongoing, evolving concept. I know it is also a studio… What is the idea behind World Food?

JP: Oh, let me clarify that convoluted history. You are right, it was the title of a studio, but just in the spirit of say, naming a yacht. We didn’t even break a champagne bottle on the door.

It was somewhere to have our mail delivered when a group of us were occupying a space together in the city. We threw a couple of spontaneous exhibitions and limbo dances, there were some screenings, not much else. It was nice though, important – it’s good to name things. We were receiving a great deal of mis-directed post that revolved around international cuisine and travel photography.

Actually, back then, I suppose three or so years ago, we had planned to use part of our studio as a shop-front to sell books we liked. Now that we have a mildly stable position to use (Y3K) and we are all not on the other side of the world, James and I have decided to put the World Food idea into play. We designed a book trolley, powder-coated it Smurf blue, and opened in the gallery alongside Marco Fusinato’s Stolen Library project in early April.

The idea is a simple one: to introduce a selection of intelligent and inspired books, journals and artist editions to Australian audiences, with the hope of encouraging intelligent and inspired reading, writing, book design/production/circulation, reflection and discussion. Well, that seems simple. We focus particularly on printed matter from small publishing houses, artist-productions and critical text, especially in the arts, as this is what we are involved in ourselves. It seemed like a smart thing to do – rather than order the one copy of a journal we would be getting for ourselves (considering the embarrassing void of such publishing in any shop here in Melbourne), add some more copies to the order and pass on the good word! We are building it from there, and the response has been encouraging. We also get to work with and support a lot of our friends overseas as a result. It is also a mobile shop, a shop on the internet, a book club to follow for the Winter, and the best book shop in Australia.

TC: What can one expect to see from Joshua Petherick in the future?

JP: I’m adjusting to the bitter cold of my studio after being in Mexico by stretching some linen, and messing around with plotting these ‘scanner videos’. Just working towards some shows late in the year and early next, and finishing up a footnote-type book to posthumously accompany my show with ACCA. Also running this series entitled Screens with Nicholas Mangan, designing new fabrics for Worthis, and selling good books!

Joshua Petherick

Next story: I Scream, You Scream – Van Leeuwen