Videosmith

Text: Amelia Stein Images: Sam Smith

Text: Amelia Stein Images: Sam Smith

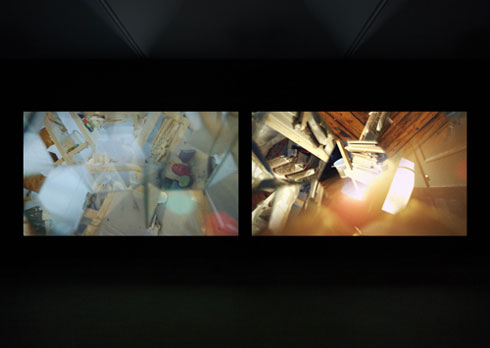

Recently, Sam Smith screened a single-channel video of his new work Cameraman at the Art Gallery of New South Wales. The video also exists in two-channel form, which was being played at the same time in another room in the gallery.

Cameraman was shot over two weeks in Berlin and takes place between the Cameraman’s apartment, an artist’s studio and a cinema. The original version splits the screen, moving its audience between these locations, as another film is shot and plaster models of lenses made. As the communication of space and structure becomes clearer, linear time is discarded.

It is apt that, at a particular point, two versions of Cameraman were running concurrently in the AGNSW. As Smith explains in our interview, his intention with the one-channel version was not simply to re-purpose the existing work or tighten the narrative, but to create something entirely new through editing. This means new spaces opened within the same footage, and new possibilities for the film and for film as a medium.

Millie Stein: I would argue that video is not just a medium for you, but a concern and a theme. What do you think of this idea?

Sam Smith: I am interested in exploring what video and especially cinematic language offers when broken down and combined in new ways. Up until this year I had worked exclusively with digital video and a primary concern was with the qualities of special effects and how the apparatus of digital video operated as a tool to transform and distort. With Cameraman (2011) I shot part of the work on 16mm film which corresponded to a more detailed investigation of the language of editing and the physical qualities of cinema in contrast with the form of sculpture.

There are fundamentally two things operating with video: time and space. I think of video as being three-dimensional and the act of making images is about constructing space. And then you have film editing which is time-based.

MS: Can you tell me a bit more about how you approach editing, when considering this idea of film as three-dimensional, even sculptural?

SS: With the case of multi-channel works that I’ve made the spaces between and around the screens become a factor in the edit. This includes the physical gap in the installation and the void as it relates to the work’s narrative or architecture. The former relates more to how I would like to direct the movement of the audience and the later is to do with the three-dimensionality of the screen-space. With Cameraman (a two-channel installation) I was very aware when editing of how the characters moved between the two screens. I see it as two windows to the landscape of the video. Sometimes a single shot is presented across both but predominately they are used to draw together narrative and spatial elements. During a large part of the work the two screens are also separated visually with 16mm film footage appearing on the left channel and digital on the right. In this way you could say there is also a temporal gap between the screens created by the media.

MS: I saw Cameraman both as two-channel and single-channel. Is it possible to say if one worked ‘better’ in terms of that idea of creating impossible space? or were there different intentions for both?

SS: There were different intentions for the two versions and therefore they employ alternate shots and edits. I label the single-channel edit as the cinema version and it was specifically made for only that environment. Because Cameraman uses film theatres as key locations I was interested to introduce the work back into that universe. The idea of impossible space is linked to both versions but whereas the cinema version must rely on montage, the gallery edit can play with space across screens to physically direct narrative in a conceptual way.

MS: A lot of your work contains scenes that could potentially stand alone as stills. Can you explain the importance of giving motion to these images?

SS: This is an interesting point. For me it comes back to the idea of montage, or the grouping together of single images or shots into a sequence. In Cameraman, part of the work depicts the construction of plaster cast static forms using a hand-held, documentary style of shooting. Perhaps a way to see the translation of static to moving images might be to think about the process of animating a sculpture. I’m interested in the spatial advantages of montage also. The ability to create alternate architectures and impossible spaces through linking two or more filmic locations. Cameraman uses this device more than once in order to present a fluid idea of space.

MS: As well as time and space, I would say that action/narrative is a third possibility or component of video. How important is narrative to your work?

SS: I like the idea of narrative being described as action as it minimises the notion of story and highlights movement instead. In the past the importance of narrative has fluctuated but in Cameraman it was part of the production methodology. For the first time I wrote a script and shot the greater portion of the work during a dedicated two weeks. In this way the production mimicked a small scale film shoot. It was my intention to do so, but then to lose this focus in the edit and look at an expanded idea of narrative and form during the post-production and install.

Images 1-7:

Cameraman (2011)

4K and Super 16mm film

transferred to HD video, stereo, colour, 16:9

31:14 minutes

Courtesy the artist and GRANTPIRRIE, Sydney

Image 8:

Into The Void (2009)

Single channel HD video

Stereo, colour, 1080p, 16:9

5:50 minutes

Courtesy the artist and GRANTPIRRIE, Sydney

Image 9:

Permutation Set (2010)

4 channel HD video installation

Stereo, colour, 1080p, 16:9

20 seconds times 16,777,216 permutations

Courtesy the artist and GRANTPIRRIE, Sydney

Sam Smith

Next story: Berlin Calling – Benjamin Lichtenstein