The Passed Note

Text: Sinisa Mackovic Images: Conor O’Brien

Text: Sinisa Mackovic Images: Conor O’Brien

Conor O’Brien is really interested in architecture. His brother Liam, an industrial designer, studied architecture for a couple of years. Patrick, who is the next one down, studied art and is obsessed with architecture too. Their youngest brother Brendan is studying architecture and likes team sports. Their father is a town planner who has a huge collection of National Geographics.

Conor is not interested in purist ideas about photography. He shoots on film but uses the computer as a dark room before getting his prints made. His photography is an art practice that exists through distancing himself, through small decisions, through meticulous sizing – resulting in poignant, physical pieces of art. As he says, “It’s about trusting, but second guessing yourself”.

Rob Milne and I recently worked with Conor on his new publication, The Passed Note. I sat down with Conor to speak about the development of his art-making practice.

Sinisa Mackovic: What goes into creating a body of your work?

Conor O’Brien: It’s visual thinking, in a way. I’m always looking for things that will represent an idea. It’s not always apparent at the time and whether or not it will actually translate in the end is where a lot of the thought goes. It also comes down to trying to separate myself from the moment a bit – to have some distance and be objective. Then it’s about bringing together different images that may work together as a body of work. These days, I’m very conscious of each work standing up on it’s own. I don’t show an image or put an image in a book unless I believe it can stand alone as a physical artwork.

SM: It needs to have that validity?

CO: Yes. It comes down to this being my art practice. I am interested in making these physical pieces, these artworks that exist at a specific size.

SM: The size of your photographs is as much a part of the work as what’s actually in the composition of the photograph.

CO: Again, it comes down to the physicality of it. When you’re standing in front of a framed picture, you’re standing in front of the primary piece of artwork and changes in scale affect how you connect with it. There is a really good interview with the painter Konrad Klaphek, where he describes a similar thing with scale. He says that if you’re painting a key, an intimate object, then you make the painting small. But if you’re painting a bulldozer, you make the painting big. It’s exactly the same in my work both physically and in a publication. All of this is quite meticulous but it’s just about how you experience the image.

SM: Do you relate how your pictures are viewed on a wall to how they are viewed in a book? Is it connected? Do you see them as different experiences?

CO: They are different experiences but both are important. When exhibiting, the decisions you make about which picture goes where are all going to influence how the room and the work is experienced. A book is the same. The sequence in which the images run tells a story. That story is subjective to whoever is reading it, and they bring with them all of their experiences. What I’m interested in when sequencing a book or an exhibition is creating connections that people can interpret their own way. I guess what it comes down to is that everything is considered.

SM: Has moving around affected your work? You grew up in Perth. You were in Melbourne for a while, Canada for a while, now you’re in Sydney.

CO: Each time you do a big move you grow as a person, learn new things and are confronted with new situations. My partner, Amanda [Maxwell] and I have moved around together for a long time. She grew up moving around a lot. We’re trying to stay a bit more settled these days with our little girl, but who knows. The different places that I’ve lived at different times have helped define the work I’ve made.

SM: So before you were documenting something but you aren’t any longer?

CO: I might have started out that way, but now it’s definitely not about that. It is just about expressing ideas. There is definitely no single place that these photos are describing.

SM: Or even a time?

CO: Not really a time either. It’s not that I want the images to be timeless but I hope that there is a timelessness to them. You couldn’t necessarily pinpoint a particular time and place in this world from these photographs. It’s about an inner world.

SM: The titles of your photographs are usually very simple, basically just naming the subject. I think that conveys your point.

CO: My titles are quite dull, in a way. It’s just a basic description of something, rather than putting my own interpretation into people’s minds. I don’t want to taint someone’s interpretation of a photograph.

SM: However, when you title a series it’s more poetic.

CO: Absolutely. It vaguely sums up a feeling of the whole body of work. This body of work, The Passed Note, hints at the feelings that I had as a teenager and the emotions attached with working out what the world is about.

SM: I’ve noticed that there are less and less people present in your photographs.

CO: It’s more that I’ve become more comfortable expressing ideas with spaces and objects. I’m after the not-so-obvious things. The pictures of people that I have made in the last few years are almost anti-portraits. They’re close but they’re not giving it all away. For example, the picture ‘Eyes Closed’ is as close as you can get to a portrait but she’s not letting you in. She’s in her own world. Images like that work to show an opposite to the popular imagery that’s in magazines and the internet. It’s showing a different side, not really an antidote, but it’s holding back on the obvious. But I am still interested in people, in portraits and populating those spaces in an abstract way. So people are still crucial even if they don’t appear in many pictures.

SM: What sort of focus are you trying to create by generally only having one subject in a photo?

CO: It’s about having a personal connection. Whether it’s to an object, a landscape, a room or a person. It’s almost like a portrait of a landscape, or a portrait of an object or a space. It’s an intimate, personal experience.

SM: You’ve published every one of your bodies of work in a monograph-style publication. This body of work, The Passed Note, is being shown in its entirety in a book before it has been exhibited as a whole. Publication seems to be a big part of your final outcome.

CO: Absolutely. I love artists’ books. It’s almost like the book is the document and the physical work is the primary experience. I really see having a publication as up there with making the artwork. My previous books were always done on very limited budgets. Tom [Jeppe] from Serps Press got behind it and published them. I wanted high quality, photographic reproductions and so we made these stapled booklets without covers, which was the cheapest way that you could do high quality publications. Over the years we kept finding ourselves in the same situation of wanting to put out this new work but still having a small budget. We ended up with quite a few of these booklets so we put it them together into a box set. It was a nice way to finalise that stuff and move on.

With The Passed Note, I guess it worked as an artist book since you guys gave me the freedom to edit and design the content but it worked the other way as well, collaborating on the final object. A part that I love was including Amanda’s story The Butterfly Knife. I feel that Amanda’s writing and my photographs are often talking about the same things in different ways. I love the idea of having one of her stories – not necessarily to accompany, but to compliment the work. It covers some of the feelings and ideas that I had about the work in an indirect and non-literal way rather than, say, an essay about the work. Hopefully when people read the story they will appreciate it as its own thing, because even though it’s an important part of the book it was actually written before this work was made.

SM: How important are images that you see and collect daily?

CO: You can absorb these things and sometimes they find their way into your work. There are a lot of artists that jump mediums. Sometimes they do it really well but it’s almost harder and more of a challenge for me to stick with one medium. For instance, I’m interested in minimalist sculpture so a part of me thinks I could start making minimalist sculpture… but I’m really most comfortable with photography as the medium that I can express myself with. There is this sculpture owned by the Art Gallery of NSW, which is two white busts on plinths looking at a third one smashed on the ground. I’ve always been really taken with it and it has come out in my work through the picture ‘Broken Horses’. I had bought those horses intact from an op shop, had them on my desk for a while and even photographed them a couple of times. One day, I accidentally knocked them over and they smashed. I took the photo and although I didn’t make the connection to the sculpture at the time, afterwards I realized there was a similarity.

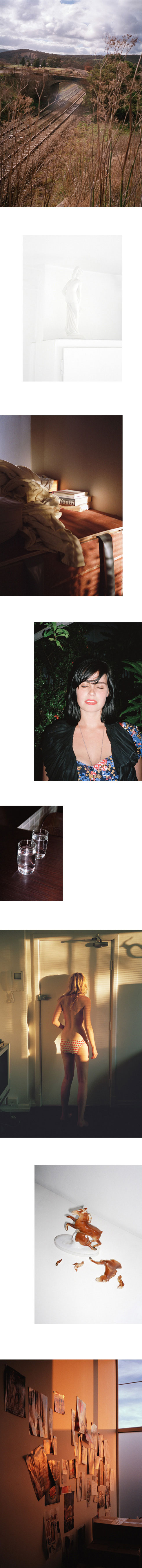

SM: The ‘White Statue’ photograph is on the cover of the book. It’s kind of become the defining photo for me. Apart from being on the cover, it sums up that focus aspect we talked about. Do you think it sums up the body of work?

CO: It’s definitely a favourite work of the series. It’s a portrait of the object and the space that it occupies and it carries that feeling, but it doesn’t necessarily define it for me. This is also quite interesting [referring to the photographs ‘White Statue’ and ‘Looking’]. They both came about on their own and they’re both their own pictures but there is a story between them. It’s what happens when you start putting images together in a sequence, into these non-linear narratives.

SM: That’s one of the more interesting parts of making a book, the sequencing process – dictating how the story is told.

CO: I think that what makes an artist’s work their own are all the small decisions that go into every part of the process. For me, it’s not even really the taking of the photo because I am by no means a photo nerd guy or that interested in cameras. I’m interested more in the way I connect and communicate using images. I guess that’s what I do, I communicate and give context to these images.

SM: Tell me about Montana.

CO: It’s something of a mystery.

Images in order or appearance:

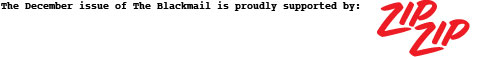

Train Bridge, 2008/09, C-Print, 89 x 127cm

White Statue, 2008/09, C-Print, 35 x 51cm

Youth, 2008/09, C-Print, 51 x 72cm

Eyes Closed, 2008/09, C-Print, 51 x 72cm

Two Glasses, 2008/09, C-Print, 35 x 51cm

Looking, 2008/09, C-Print, 71 x 101cm

Broken Horses, 2008/09, C-Print, 51 x 72cm

Wall, 2008/09, C-Print, 71 x 101cm

Installation: Points Of View, Curated by Olivia Radonich, Tolarno Galleries, Melbourne 2010

The Passed Note published by Rainoff, 2010

Conor O’Brien launches The Passed Note with an exhibition at Monster Children Gallery on Sunday December 5, 2 – 5pm and in February 2011 in Melbourne.

Next story: The Babe In The Woods – Washed Out